Modern War

While the many wars of the late 1800’s and the Great War all had to contend with some level of mechanization, it would seem to me quite uncontroversial to say that World War II was the first massively mechanized war. From the blitzkrieg that opened it to the nuclear bomb that brought it to a close, nearly every movement of the conflict was built off of a technological backboard that was once merely a loose cross-wiring of brain tissue in some strategist’s head just 30 years before. Where pilots once fired rifles from the saddles of biplanes like cowboys of the sky, when American troops returned to France they themselves could be counted among the many payloads dropped into its fields and hills, carried on the wings of “flying fortresses.”

Not to mean specifically the B-17 Flying Fortress, but the paratrooper laden Douglas C-47 was arguably a beast of like nature when compared to the previous generations of war planes.

While the story of how modern warfare war came to be starts many years before Germany’s invasion of Poland, by World War II the new way had been fully established: through technology, war had been democratized.

What do I mean by that? How can war be democratic? From a literal sense this is absurd: the most powerful militaries still follow rigid hierarchies where the one on top gets final say. Of all the ways democracy has spread in the world, military institutions remain the single most stubbornly autocratic organizations in society.

However, I’m not talking about a democratization of military authority. I’m referring to a “democratization” of killing ability.

War has always been a source of dread and fear for those who engage in it—of course this is true. Yet, it was also for many a source of glory and pride, a chance for heroism, a show of strength and skill. And more than that, it was a direct contest of human wills.

Whether the cause of the conflict was just or petty, its resolution came about through man meeting man and demonstrating who was the better swordsman, better marksman, better tactician… Whatever the deciding trait was, the better man won. While exceptions happened, they were just that—exceptional. For lack of a better term, war was a “meritocracy”… And more to the point, violence was.

This changes with modern war, where the dominance of the “better man” has been overturned.

In modern war, death comes not from a blade you can parry or arrows you can deflect with a shield, but from small bits of lead flying too quick for the eye to track from small bushes on the hills, it comes from strange birds untouchable in the sky dropping metal fruit that can collapse whole villages, it comes from starving children who were given a funny toy and a request to entertain the visitor with it. It comes from an old man in a chair on the other side of the world, and when it comes it will take your whole city, too.

Where once security came through the literal strength of one’s arms, power that can decide life and death now sits in machines even an infant could operate—if we didn’t go out of our way to reintroduce obstacles to the process.

The infirm, the nursing mother, the child, the near, the far: in modern war, every arm can be the one to deliver death’s steely grasp.

With rocketry our weapons can reach the other ends of the earth. With automation our weapons can act by themselves. With nuclear fission, gathering an army a million strong is how you lose.

The hills have eyes, the doors have swords, the sky can burn: in modern war, no sanctuary is free from death’s reach.

The mighty man’s monopoly on death has been broken. Modern war has become democratic. The violence of every voice can be heard—and their words bring terror. Sure, the man with the greater “bank account” can still use that to gain an advantage at the macro level (how “big” that advantage is relative to the cost is another story), but that just proves my point.

Some people may still want to believe our soldiers can be modern knights, citing the many tales of heroism in WWII as an example. And, to be sure, we do still get plenty of heroes, but a knight is another matter. Look just one war later: did young boys sing the songs of any veterans of the Korean war (genuine question)?

Look at Vietnam: even our mythical warriors from that era, known to most through the zeitgeist of Hollywood, are broken and terrified. And this isn’t just a matter of where you fall on the political division that pervaded the conflict, everyone likes Rambo and Apocalypse Now.

Anyone who doesn’t should not be listened to as far as movie tastes go.

In modern war, flesh is a liability. It is too soft and slow on these battlegrounds dominated by machines. Our support equipment can be hostile to human life. I learned this when a friend in the military described the severe nausea suffered by passengers of armored vehicles carrying high-powered radios. Even the terrain that used to require a human touch—the jungles, caves, and large buildings—are becoming traversable and thus conquerable by new drone technology.

Men on the frontlines no longer wage war—they merely try to survive it.

Of all of the woes of the modern world, the mechanization of warfare has arguably been the most dehumanizing poison of it all. We envisioned a world where the natural gifts of a man could no longer grant him exclusive rights to the spoils of war… and that’s what we got.

So, it should come as no surprise that people now fantasize about becoming the giant machines—in a way.

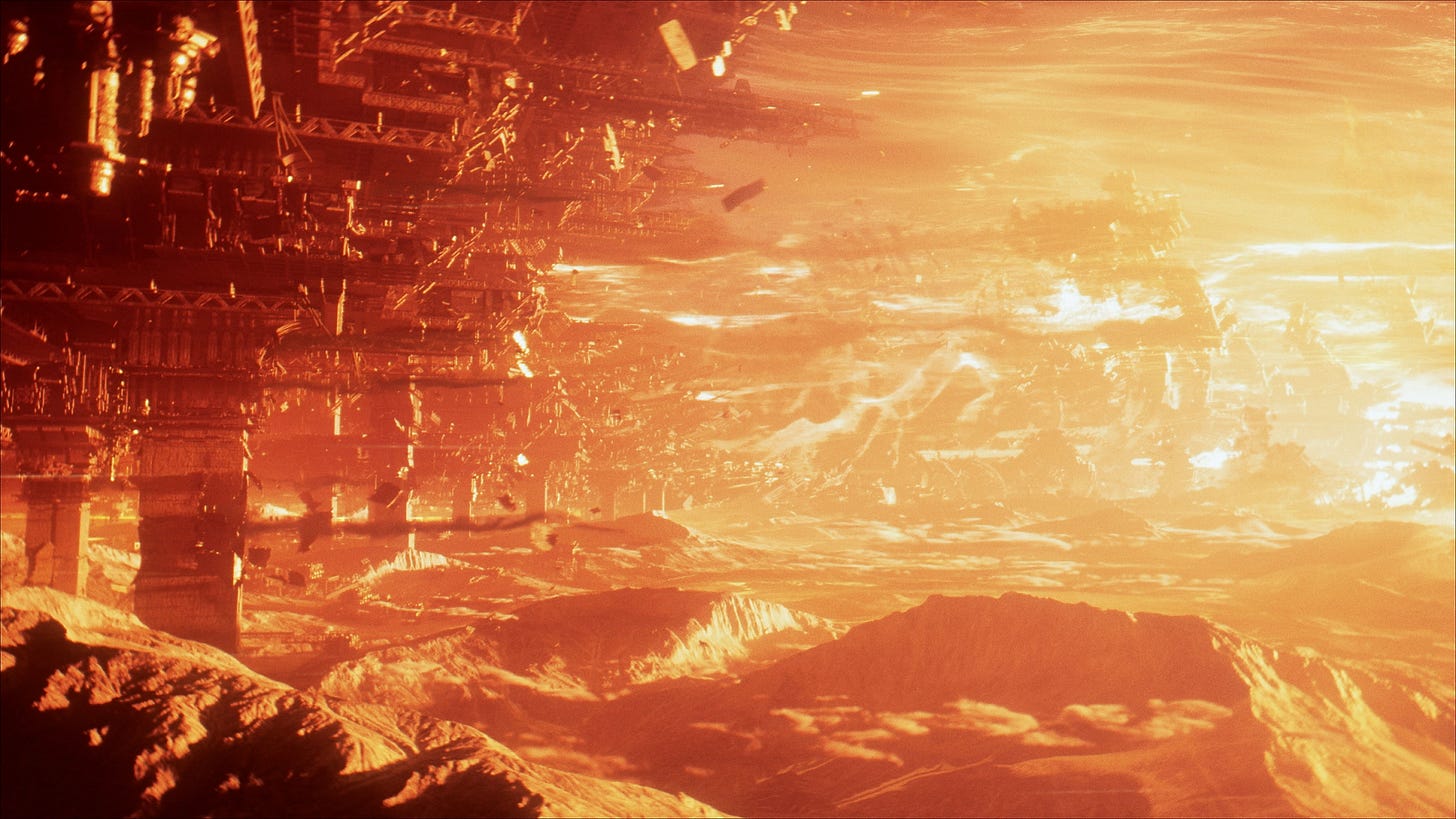

Yes, this article is about those mechs.

The Fantasy

The idea of a mechanical man is of course older than WWII. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis being the most prominent example I think of for early fiction about a “machine man” (or woman in that case) born of technological means, and I’m sure a more well-read sort could go back further.

However, it is in the Cold War era that we see the rise of a specific form of metal man which we now call “mechs.” Rather than attempt to imitate the soul with circuits and software, the mech is controlled by an already very human pilot. Whereas robots and androids are symbols of the strange relation of technology and procreation—an “other” that reflects our nature for introspection—the mech is an extension of man’s will.

At its most basic conceptual level, the mech was once the next logical step up from a tank: take all of the advantages of armored vehicles with heavy firepower and try to give them all of the flexibility of a human soldier. It’s easy to see how the concept became popular in speculative fiction (and in actual military research) following a war that placed an unprecedented number of men into little metal boxes with big guns. If the often inelegant “wheeled tank” inspired awe and gave the pilots a sense of invincibility, one could only imagine the high a pilot would experience at the helm of a contraption that fused all of that power—and more—into a form as natural to maneuver as our own bodies.

Physics, however, has so far judged such wild ambitions to be mere daydreams. Every real-life attempt to build one has produced—at best—a slow, lumbering brute barely able to support its own weight. Such prototypes could do nothing on a battlefield except draw the first salvo of enemy fire.

It’s almost as if the laws of nature mock us the way great steel aircraft carriers can roam the oceans as floating islands, yet even just one metal man-o-war has proven near impossible. It really is a testament—in a way—to the complexity of man’s own biological design. In any case, the greater the scale of a machine, the less human it can be as certain ways of moving become exponentially more expensive in terms of the force and energy required to accomplish them. Even biological life has to obey physics at some point: there’s a reason our planet’s largest organisms live in the supporting pressure of the ocean.

Despite all of this, the dream does not die. The number of TV series since the sixties featuring mechs as a major element numbers in the hundreds, with seemingly another half dozen every year—if not more during the occasional boom years. And then there all of the movies, games, comics, toys, hobby models…

The popularity of mechs waxes and wanes, and they are by far and large more popular in the East than the West, but we here in the West still have our own niche of mech fiction with the likes of the BattleTech wargame and the Pacific Rim movies. Not to mention the amount of it we import: Voltron, Gundam, Metal Gear, Neon Genesis Evangelion, to name some of the most popular.

As with most subgenres, tastes begin to shift away from whatever specific interpretation got popular for a season. The genre stagnates and may even be forgotten about for a time. But, then eventually some new series or reboot of a classic comes around and the niche is thriving again.

Why is this? How do these impractical fantasy machines keep popping up in science fiction when real science can’t stop telling us how unreasonable they are? Why does every piece of media that includes them in some form display them front and center in marketing materials even when the main content of the experience may have very little to do with them directly? How did they become science fiction’s “dragon?”

The first reason is, of course, that they’re cool. They shoot flaming rockets, swing great swords and knives like talons, take to the air upon jet engine wings, can shrug off all but the most deadly bullets and lasers from their metal plated hide, and do so while standing at the height of the Statue of Liberty (or the Colossus of Rhodes).

When I put it that way, they do kind of sound like dragons… And dragons never go out of style.

Returning Humanity to the Battlefield

The second reason is that they allow an individual man to once again hold power over his fate in war. The shield of a mech can deflect bullets like mere arrows, it’s feet can shrug off all but the most violent mines, it can carry a sword into combat if the pilot so wishes and with it challenge his foes toe-to-toe like in battles of old. With the fantasy of the mech—the power and protection of the great metal shell—man can once again dance across the battlefield.

And while no one is going to claim a mech of any sort could protect the rider from a nuke, they can carry their own nuclear armaments and at least even the odds.

Mechs make war human again. Victory in battle revolves around the skills of hotshot heroes and their individual skill. It is a true resurrection of the armored knights of old. The BattleTech IP is blatant about this, depicting its pilots in a neo-feudal future full of great houses and mercenary companies.

This return to war as something humans can directly participate in is probably why so much mech fiction spends as much if not more time exploring the fundamental elements of humanity. Especially relationships, whether that’s a brotherhood of warriors, longing love interests, or the push and pull of authority—and usually all of the above. This focus on what is “human” can get downright jarring with how violent and sexual mech fiction can get, but even the stories that steer clear of depicting gratuitous content still revolve around the topics.

When I first watched the original Gundam recently, I had mistakenly assumed that a series from the late seventies would still be carried by the simplistic action of giant robots duking it out. Little did I know that Japan had moved past that years prior. Instead, Gundam is interested in the emotional weight of war on its young hero. We see him struggle with the weight of the death he deals; we see him grow cold to his pacifist mother after she condemns his way of dealing with an enemy patrol; we see him grumble against the machinations of military command as they order him and his friends on ill-explained missions; and we see him find motivation in wanting to impress a woman who catches his eye and in a growing rivalry with an enemy pilot.

The “Mecha” isn’t really about the “mechanical soldiers” after all. If it were, they would be theoretical engineering lectures, not stories. It’s about the pilots really, the machines are just an extension of who those pilots are. To put it jokingly, mecha is just Top Gun as an entire cross-media genre… with occasional bouts of RoboCop mixed in.

Depending on the level of grit the story is aiming for, it’s not uncommon for cyborg elements and extreme acts of dehumanization to also play a factor. The Armored Core series of games by FromSoft takes this tack. In its sixth entry (at least) the player never even sees a human body, just disembodied voices with callsigns instead of names and logos instead of faces.

In Armored Core’s universe, many pilots are “augmented” humans enslaved to their work by the massive debts the operations cost (whether willing or not). The player’s character in particular being so far gone at the start of the story that he has no name, only an alphanumeric designation. Yet even though that universe is so hostile to the humans that maintain their original flesh—or rather because the universe is that hostile, the story focuses itself not on the political maneuvers that initiate all of its conflicts, but rather on the fate of the “Rubiconians” whose lives are tied to the rare resource “Coral” over which the mighty corporate powers fight.

And—unlike FromSoft’s more popular fantasy RPG series, Dark Souls—this story is told through its humans first and foremost. Their presence in Armored Core may be disembodied, but its their voices—their goals and dreams—that give the player context to all of the action occurring. Enemy pilots vie for prestige within their companies, your handler plots and schemes to subvert all of the gathered factions in the conflict, the outspoken pilot “Rusty” plays the role of rival and folk hero for the Rubiconians. And while it’s rarely explicit about it, throughout the course of the story you’re given signs that the player character is gradually reclaiming that humanity he once sold.

Contrast that to Dark Souls itself where even when you can see humans on screen, they are often twisted or on their way to becoming twisted, unable to do much beyond spouting esoteric poetry, cursing everything that breathes, or further stripping themselves of any dignity. The plots are obtuse and intentionally fragmented and the world constantly reminds you that you are wandering lost and alone. The stories of the Souls games are about holding on to a dying ember of humanity rather than lighting one anew.

I highlight this just to further emphasize how central humanization is to the mecha genre. FromSoft is the company that had an item called “humanity” drop most frequently from the rats in one of their titles, yet even their take on the mech story ends with a revival of a soul in a universe sterilized by the natural end of modern war.

So, as the military industrial complex rages on and as the many branches of liberalism divide men from each other and from our heritage as people, the mecha genre will likely only grow in relevance. The metal suit is to many the means by which a warrior can finally walk back out into the open plains and not worry about getting drone striked by a bureaucrat in his pajamas on the other side of the world—at least not without putting up a fight.

Thank you to all of you who read this far. As always, I have no intent yet of getting into rigorously academic essays. However, I hope this got you thinking about something interesting, or if you think I missed something or ought to expound more on a particular point, feel free to let me know. And—of course—share it if you liked it. Never hurts to get a few more audience members!